billfried@gmail.com

Bill is a graduate of Fieldston High School and the University of Pittsburgh. He received an MA in philosophy from Brown and a Masters of City Planning from MIT. He is co-author, with Professor Joan Smith, of The Uses of the American Prison, (DC Heath). He published "Promoting Racial Integration in Housing" (The Journal of Town Planning) and "The Limits of Reform" (The Prison Journal).

His op-eds have appeared in the Baltimore Sun, the Boston Globe, the Boston Herald, the Patriot Ledger, Alternet, Truthout, Common Dreams, the Daily Kos, CounterPunch, Commonwealth Magazine, and elsewhere. He has written political satire for the Somerville Community News and for The Panther Players (Vermont NPR). He has delivered numerous commentaries on National Public Radio.

He has worked at the Open Center for Children day care center, the Back of the Hill Community Development Corporation, Lakeview Manor Tenant Association, and Law Enforcement Action Partnership. He has done video work for LEAP and as a retired volunteer for SIFMA-Now and Parole Watch in Boston. His photos have been displayed at a number of small venues in Massachusetts.

script for video

The War on Drugs was a full frontal attack on the turbulent 60’s, when unfettered state force adopted a hair trigger, us-them mentality about drug users, especially if they were activists who looked like I did at that time.

Drugs were vilified or deified. Some thought that if anyone used them, the world would come to an end. Some thought that if everyone used them, the world would live as one. I came to resent it when political or cultural protests were reduced to drug use—when drugs were fetishized.

Being stoned didn’t make our generation any hipper or more progressive than our parents were when they were high on gin, though there was something admittedly groovy using a drug that even our parents weren't allowed to use. But still, it wasn’t about alcohol or marijuana, which some could handle and some couldn’t.

Sadly, that balanced perspective didn’t prevent me, when I worked for a public housing tenant association, from sponsoring a DARE officer whose threatening, zero-tolerance approach inspired these signs:(don’t do the crime if you can’t do the time, taking one step closer to death by taking drugs”) and made for a feel good photo-op that I proudly put up on our website.

Well, I worked there long enough to see some of those kids join 900,000 of their peers, working the illegal drug market, forced to snitch on friends and family, victims of a life-threatening cat and mouse game, while police cars rolled through the project—everyone a suspect, a community reduced to a crime scene.

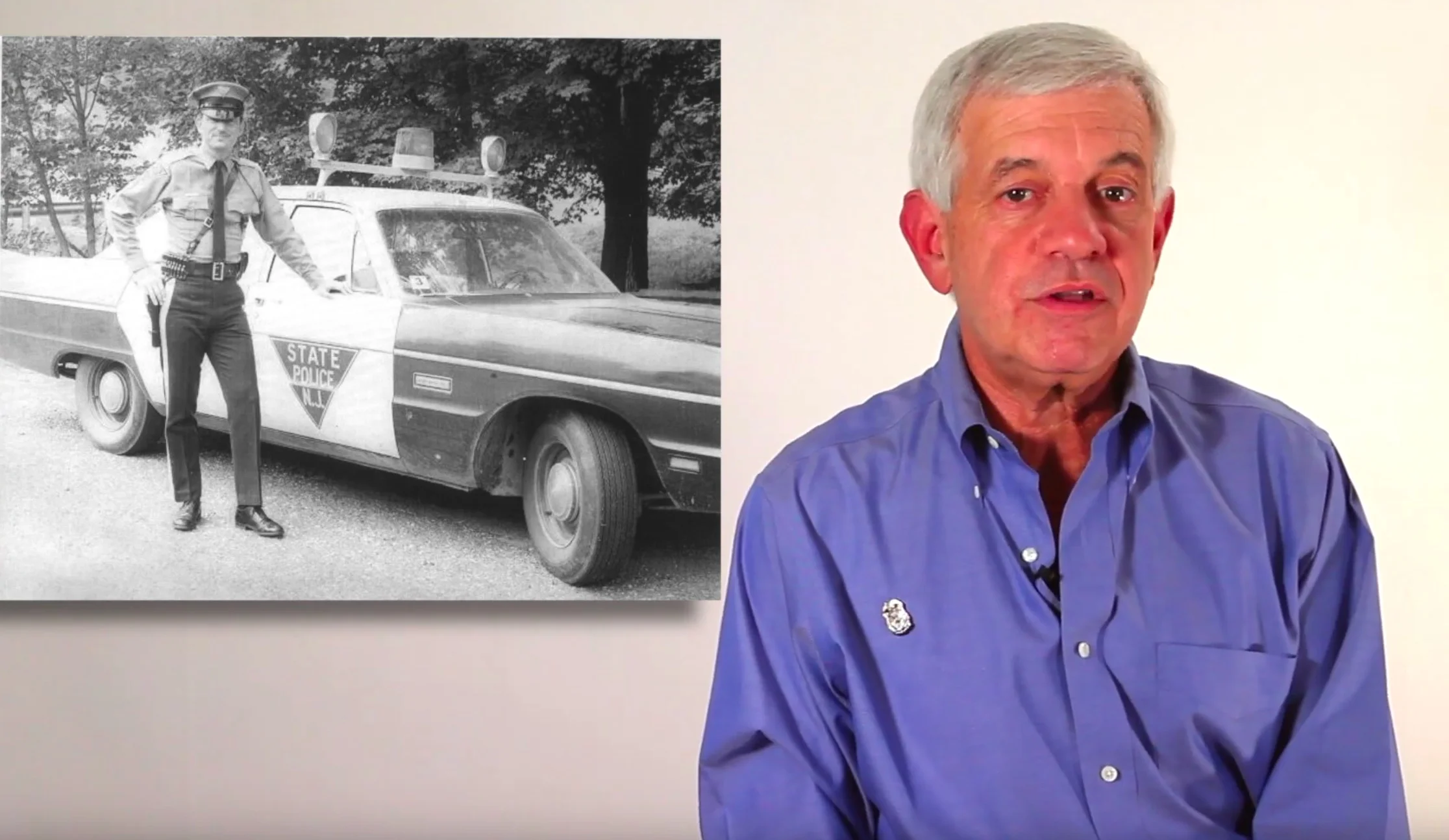

But it wasn’t until I joined unlikely allies at the then called Law Enforcement Against Prohibition that I connected the dots between so many of the problems I saw at that project and the policy of prohibition, a policy that poisons everything it touches, and touches nearly everything.

The fundamental point is that drug policy may be fueled by self-interest and hysteria, but it’s not about the drugs, which are seductive chemicals that may reveal or hide character, provide quick relief, help you see things you didn’t see or blind you to things you should see.

Indeed, the same amphetamine the military gives our soldiers to heighten combat readiness rots the minds and bodies of others. The same heroin consumed sadly but safely in other countries in a supportive, supervised facility is blamed for the deaths of thousands of Americans; the same cocaine that fuels the hard working financial and entertainment industries can fatally overtax the brain and heart. The same marijuana that helps high achievers with creativity, vision and productivity, is a dead end cloud of false wisdom for others.

And the same alcohol that may soothe and cure, can seduce and destroy. Ask drug warriors if they support the prohibition of alcohol and watch them change the subject.

We’ve survived and now mock such absurdity, including the 20th century prohibition on yet another activity said to addict our children and sap their initiative. Yes, pinball was prohibited in our largest cities.

Nobody takes these laws seriously except those whose lives are ruined by them through selective enforcement, based, as was the initial motivation, on race, ethnicity, or class.

But the tide has turned, and it's no longer a third rail issue for politicians, so how will the modern prohibitionist squeeze every last arrest and federal dollar out of yesterday’s folly?

Two strategies slow reform, both of which echo the fetishizing of drugs that shaped the 60s.

THE BIG SCARE

Pinball prohibition may be laughable, but give a moment to the parents’ real concern about their kids—some of whom probably were losing themselves in this seductive activity. Parental concern is fertile ground for exploitation, witness media coverage which labels every increases in drug abuse an epidemic, and witness professional drug warriors who point at the disease-spreading drug scene, exploding meth cookeries that send burned children to emergency rooms, and at drug dealers turning neighborhoods into killing fields. They manipulate the legitimate fears of parents who have lost children to drugs and the crimes committed to support their habit, by asking: “Isn’t this what legalization brings?

And so, after a deep breath, our unapologetic response is, no, this is what legalization prevents. Which starts the day we remove the criminal noose from those struggling with addiction.

It’s 1933 and a prohibitionist points to an illicit gin mill that has produced a contaminated product that literally blinded the person who drank it and then exploded, leaving a badly burned baby. He turns to you and asks, “Isn’t this what legalization brings?

Same question, same answer.

It’s the policy, not the drugs. Even the hardest drugs.

The second strategy parades as moderation, but in fact, it’s just…

THE BIG STALL

Today’s smart prohibitionist easily admits that addiction is a public health issue and that too many are jailed for possession (as though they always thought that). But they insist we must crack down on the traffickers.

It's called decriminalization, and it's as seductive as a drug. In fact, this describes alcohol prohibition. It wasn’t illegal to possess or drink; just to manufacture, transport and sell. Except, medical alcohol. Sound familiar? Same approach, same outcome: Beer makes the trip across the border from Mexico without violence. Marijuana makes the same trip, and blood flows.

New York decriminalized marijuana in the 1970s (the same decade they re-legalized pinball machines) yet continues every year including this one, to slam tens of thousands of mostly low-income people of color into the criminal justice system simply for having that very drug.

We can do better than decriminalization. And we can do better than just focusing on marijuana. If any popular drug is legal to use but illegal to manufacture, transport and sell, (decriminalized) will the violence stop?

Lower-income communities, primarily of color, have been torn apart, children forcibly removed from their families, sent to foster homes and often lost to the sex trade or prison for violating nothing more than these puritanical laws. We need to connect the dots from those problems to drug prohibition.

My generation perfected impatience. We believed in instant coffee and instant justice. Today's political activists make us look like turtles. They have seen workable alternatives, the foundations of a prohibition-free future that is this close; just as when we drive by a prison, we are this close to people locked inside for something we or our friends or our children or our parents have done with a wink and a nod and impunity. Every non-violent inmate who broke only these laws is a victim in need of restoration. They wait on us, minute, by minute, by minute.

Ending the drug war’s prohibition of consensual behavior, with its inevitable abuse of the most vulnerable among us, is how today’s generation will honor and carry on the human rights movements that flowered during my youth. There are winnable initiatives nearly everywhere, waiting on our energy and power. Like others before it, this movement needs a voice and a vehicle.

You're it.

We're it.